Since the presidential election, it seems as though the very idea of truth is under assault. In an ever more volatile and uncertain world, many people choose to live in media bubbles that reflect their biases and the mental habits that keep them in their comfort zones. Resisting complexity, many curate their realities by focusing on certain viewpoints while ignoring others. Fictional news stories take on the status of facts and are weaponized across social media, while actual facts are ignored or labeled false. Across vast swaths of the U.S. population, in fact, expertise is routinely downgraded and demeaned, so much so that the ability for Americans to agree on a consensus reality seems more and more difficult to achieve. This of course has tragic consequences for our civic and political lives. If we no longer value facts, it means that both the rule of law and democracy itself are in grave danger. So truth becomes an especially important topic for us now – because the possibility of justice in our country, and our world, depends on it.

Upon reflection, this assault on truth has been slowly building for years. But it took the election of Donald Trump to make frighteningly clear the civic consequences of living in a world in which the truth is not respected. But a community denial of truth — which is what we can call it when millions of people, on the political left and right, choose to believe patent falsehoods — this community denial of truth can only happen if we, as individuals, are also denying the simple, basic truths of our own lives. So I’d like to explore the idea of the importance of holding to the truth by linking a mass denial of truth with the personal tendency we all have to value or follow that which is not true.

In this context I’ll reference a famous expression from Jesus – ‘the truth will set you free’. Such a timeless and profound expression that directly connects to the practice of mindfulness. Because when it comes to mindfulness, it’s all about becoming free by seeing the truth. One of the things we can say about the teachings and practices of mindfulness is that they are designed to help us live in alignment with the truth, and by doing so, awakening us to that truth at ever deeper levels.

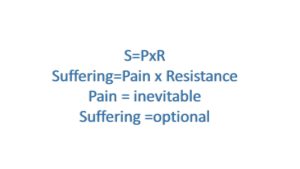

So if you think about awakening as the realization of truth, then abiding by what is not true, worshipping “alternative facts,” is the opposite of awakening, or unawakening. So to the extent that we value what is false, is the extent to which we are moving in the direction of darkness, unconsciousness, and suffering.

As individuals there are many ways that we value illusion over truth. These are the very common tendencies that we all have as fallible human beings. Tendencies that may keep us from awakening to reality – whether that’s the reality of global warming or the reality of our own mortality.

Years ago when my hair started to turn gray I resisted the fact. I wasn’t ready to have gray hair! So I dyed it. I loved what I saw in the mirror. Suddenly I looked like my old self. My friends told me they liked my new dark hair. It was great. I was in denial about the natural aging of my body and I was loving it! Then one day my girlfriend told me, “Bill, your dyed hair looks really fake.” I was outraged that she felt that way. I objected vigorously, pointing out that all my friends had told me my hair looked good. And she replied, “They’re just lying to make you feel good.” Suddenly it hit me: she was right. My hair did look bad. Gradually over time I let go of the need to maintain dark hair.

Now I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with dying one’s hair. But for me, I saw the way in which I wasn’t living in alignment with the truth of my own aging, the truth of my body’s changes….and there was suffering in that denial. My desire to maintain dark hair revealed a tension in my psyche about needing to appear another way…a tension that fell away when I allowed my hair to be just as it was. When I let my hair turn gray, that was a moment of freedom. That was a moment of living in alignment with truth.

Then there are the ways that we curate experience to promote an idea, a product, or ourselves, by highlighting certain facts and withholding others. In this regard I think of the way the term mindfulness is now being used in our world. Especially in the corporate world. Although mindfulness is essentially about recognizing the truth of reality with clear comprehension and wisdom, in the corporate world those lofty goals are pretty much sidelined in favor of a key management deliverable: greater focus and productivity. Yes, mindfulness can help you achieve greater focus, but the purpose of that focus has always been intended for the work of awakening, not for the bottom line. Also, mindfulness cannot even really take place unless there is a baseline of ethical conduct on the part of the practitioner of mindfulness. Yet how often do secular mindfulness programs talk about the importance of ethical conduct? Will you ever get a discussion of, say, sexual misconduct in a corporate mindfulness class focused on performance? Probably not.

The problem with the selective editing of mindfulness is that when it is divorced from ethics and wisdom it quickly loses its context and its meaning as a powerful tool for personal transformation and becomes just another useful training technique.

Getting even more granular about the ways we live apart from the truth is the idea of lack of presence. Lack of presence is a common ailment in our hyper-connected 24/7 media-obsessed world. Being so preoccupied by blinking notifications on your phone that when you descend a flight of stairs or walk down a street you’re not really experiencing it. The truth of the situation, the physical sensations, the way your hand reaches out for a door knob…the simple, basic aliveness of a routine moment…We’re not present for those moments so much of the time. And not just because of social media. But mostly because of the storms inside our own minds. So in a sense by not being present for the routine moments of our lives, we’re predisposing ourselves to living in a virtual reality composed of our habitual thoughts and deep-seated tendencies. Living in a world of our own personal alternative facts. And you could say that to the extent that we’re present, landed in the actuality of the here and now, is the extent to which we are living truthfully.

In fact, I’m convinced that if everyone could open a door or descend a flight of stairs with complete presence, we would have a totally transformed world politically and in all other ways.

When there is so much pressure in our world to chase after what isn’t true, to mesmerize ourselves with alternative facts, or myths that are self-serving – from what our politicians embody to the urgency of getting ahead in our corporate worlds to our routine lapses of presence with everyday reality – how do we resist this powerful tendency to step away from the truth?

Resistance is what it’s all about. Collectively, there is a beautiful resistance that’s been happening throughout our country to the regime that took power in January. A beautiful resistance consisting of marches, calls, donations, organizing, lawsuits, and judges reasserting the primacy of the constitution and the rule of law. Private citizens and some great people in Congress are actively resisting. These are all examples of honoring the truth, of resisting alternative facts. As individuals, our daily mindfulness practice is critical in resisting the denial of daily experience by losing our presence. By practicing every day, we are more likely to be present for what it feels like to grab a door handle, walk down a flight of stairs, or have an engaged conversation with a friend. Our mindfulness practice helps us live in alignment with the truth of our bodies, minds, and hearts, moment by moment, so that the possibility of awakening is never far behind.

Waking up with the truth is not a static event that happens on Monday and can then be ignored the rest of the week. Waking up is an activity, and it’s an intention. It’s something that we need to keep doing…until we’re completely woke.

Perhaps the most fundamental fact of our aliveness is that from the moment of our birth to the moment of our death, we are breathing. Yet strangely enough, we routinely take the breath for granted and forget about it. Our attention instead is gripped by our to-do lists, our racing thoughts of gain and loss, our interactions with the world. Many people I’ve worked with over the years, when describing a stressful situation, cannot recall at all how their breath felt during the event. The fact is, the breath is a vital ally in the practice of mindfulness. Because it is always available, and because its shifting nature reflects our moment to moment state of being, the breath is our portal to understanding, healing and well-being.

Perhaps the most fundamental fact of our aliveness is that from the moment of our birth to the moment of our death, we are breathing. Yet strangely enough, we routinely take the breath for granted and forget about it. Our attention instead is gripped by our to-do lists, our racing thoughts of gain and loss, our interactions with the world. Many people I’ve worked with over the years, when describing a stressful situation, cannot recall at all how their breath felt during the event. The fact is, the breath is a vital ally in the practice of mindfulness. Because it is always available, and because its shifting nature reflects our moment to moment state of being, the breath is our portal to understanding, healing and well-being.

I had been looking forward to celebrating the end of the year and the start of 2017 at a party with my partner and some friends. Instead, I spent the day in bed, swamped with fever and chills, tormented by an incessantly dripping nose and a vicious hacking cough. I was sick for about 6 days overall (and in fact am still recovering). While that is not that long of an illness it did provide me with plenty of time to contemplate the nature of healing, and the relationship between physical and mental wellness.

I had been looking forward to celebrating the end of the year and the start of 2017 at a party with my partner and some friends. Instead, I spent the day in bed, swamped with fever and chills, tormented by an incessantly dripping nose and a vicious hacking cough. I was sick for about 6 days overall (and in fact am still recovering). While that is not that long of an illness it did provide me with plenty of time to contemplate the nature of healing, and the relationship between physical and mental wellness. If you practice mindfulness meditation, you’ve had this experience: you are focusing on your breath, one inhale and exhale at a time, when suddenly a compelling thought arises, distracting you. Maybe the thought is about work, or a relationship, or the vacation that starts next week, or whatever. That thought then leads you down a series of mental rabbit holes until – five minutes in – you realize that you’ve completely lost the breath. It can be humbling to realize how little control we have over our minds. Those thoughts are so compelling!

If you practice mindfulness meditation, you’ve had this experience: you are focusing on your breath, one inhale and exhale at a time, when suddenly a compelling thought arises, distracting you. Maybe the thought is about work, or a relationship, or the vacation that starts next week, or whatever. That thought then leads you down a series of mental rabbit holes until – five minutes in – you realize that you’ve completely lost the breath. It can be humbling to realize how little control we have over our minds. Those thoughts are so compelling! In meditation, when things don’t go our way, we tend to resist. Feeling restless? Then fidget incessantly as a way of not feeling the restlessness or what may be behind it. Have a hard time focusing on your breath? Then berate yourself as a bad meditator and despair at ever getting “good” at the practice.

In meditation, when things don’t go our way, we tend to resist. Feeling restless? Then fidget incessantly as a way of not feeling the restlessness or what may be behind it. Have a hard time focusing on your breath? Then berate yourself as a bad meditator and despair at ever getting “good” at the practice.

You probably know the feeling. It’s after lunch and the day seems to drag on and on. Your energy level is low, and you can’t concentrate on your work. You aren’t getting anything done, and there doesn’t seem to be anything you can do about it. You feel like taking a nap, but of course that’s not possible at the office. The afternoon doldrums are a well-known challenge to the work day, with some 28% of employees reporting falling asleep or getting very sleepy at work, according to the National Sleep Foundation. But there are ways of working with this listlessness. Here are five ways to manage your energy during the afternoon:

You probably know the feeling. It’s after lunch and the day seems to drag on and on. Your energy level is low, and you can’t concentrate on your work. You aren’t getting anything done, and there doesn’t seem to be anything you can do about it. You feel like taking a nap, but of course that’s not possible at the office. The afternoon doldrums are a well-known challenge to the work day, with some 28% of employees reporting falling asleep or getting very sleepy at work, according to the National Sleep Foundation. But there are ways of working with this listlessness. Here are five ways to manage your energy during the afternoon: Many meditation teachers say that there is no wrong way to meditate. That showing up and doing the practice is what’s important. Having said that, the following list of common mistakes or misconceptions about meditation keep showing up in my teaching with students. They are:

Many meditation teachers say that there is no wrong way to meditate. That showing up and doing the practice is what’s important. Having said that, the following list of common mistakes or misconceptions about meditation keep showing up in my teaching with students. They are: