What do you have a hard time letting go of? Perhaps it’s letting go of the little time-honored personal rituals that you enact in your life. Like always grating your cheese or chopping onions a certain way. Or always listening to a certain program or reading certain publications to get on top of current events. Or making sure you always get to a movie early enough to watch the trailers. Or perhaps it’s the idea that you always need to be the best at something, the smartest person in the room? Or that you always need to be right? Or that your body should always look a certain way? Or that only certain people are worthy of your consideration? Maybe it’s hard to give up a plan, or an ideal, or a relationship. But think about this. When we talk about letting go, what exactly are we letting go of? What’s behind the letting go of, say, the idea that you always need to be right, or chop your onions in a certain way?

What do you have a hard time letting go of? Perhaps it’s letting go of the little time-honored personal rituals that you enact in your life. Like always grating your cheese or chopping onions a certain way. Or always listening to a certain program or reading certain publications to get on top of current events. Or making sure you always get to a movie early enough to watch the trailers. Or perhaps it’s the idea that you always need to be the best at something, the smartest person in the room? Or that you always need to be right? Or that your body should always look a certain way? Or that only certain people are worthy of your consideration? Maybe it’s hard to give up a plan, or an ideal, or a relationship. But think about this. When we talk about letting go, what exactly are we letting go of? What’s behind the letting go of, say, the idea that you always need to be right, or chop your onions in a certain way?

What we’re letting go of is really a habit. And a habit is really all about clinging. But when we cling to a habit, what are we clinging to? We are clinging to what we know. We’re clinging to the known world. To what is familiar and comfortable.

Buddhism always talks about not clinging….that’s because to cling is also to suffer. As spoken of the diligent practitioner who practices mindfulness, it is said, in the refrain to The 4 Foundations of Mindfulness sutta, “And he abides independent, not clinging to anything in the world.” That phrase is said over and over again in that teaching. And the value of not clinging, of letting go, is mentioned countless times in Buddhist writings.

Even the word nibbana, which we usually translate as enlightenment, implies non-clinging. The word literally means extinguishing the flame. What does the flame cling to? It clings to its fuel.

So, there’s a big emphasis on clinging as a cause of suffering, and not clinging, or letting go, as the gateway to freedom.

But what’s wrong with clinging? Why do we suffer when we cling?

Because everything is impermanent. If you cling to what can’t actually be clung to, you’re setting yourself up for suffering. For loss and heart break. And for cycles of reactivity that only lead to more suffering. Buddhism is really oriented towards realizing that impermanence is a fundamental aspect of reality. And letting go of the idea of permanence is what allows the new and unknown to emerge. It’s also what allows us to transform ourselves, to learn, to love, to deepen our experience of life.

And when we practice, there are many ways that we express the intention to let go.

Even with ethics. We’re letting go of ways of relating to the world that maybe aren’t ethical. When we experience wisdom, we’re letting go of ignorance.

And certainly in our meditation practice we’re practicing letting go all the time. Just to sit on your bench or your chair or cushion. Just doing that represents a huge act of letting go. I mean, what is a typical morning habit? You know, we wake up, and our minds start thinking about things. Maybe it’s…my god, this meeting I have today. How’s it going to go? Or maybe it’s, my god, I can’t believe that person is our president. The cortisol starts entering the bloodstream. By habit we want to get up, get our coffee, have breakfast, check our phones, hear the news, get started. Step onto the treadmill of the day’s routine. But if instead of doing that you sit down for 30 minutes and just try being with your breathing, that is a radical act of letting go…of the habit of the morning treadmill. Or maybe you sit at night. And maybe you would ordinarily have your glass of wine after work. But instead of doing that you’re sitting and being with yourself. That’s a letting go. It’s profound.

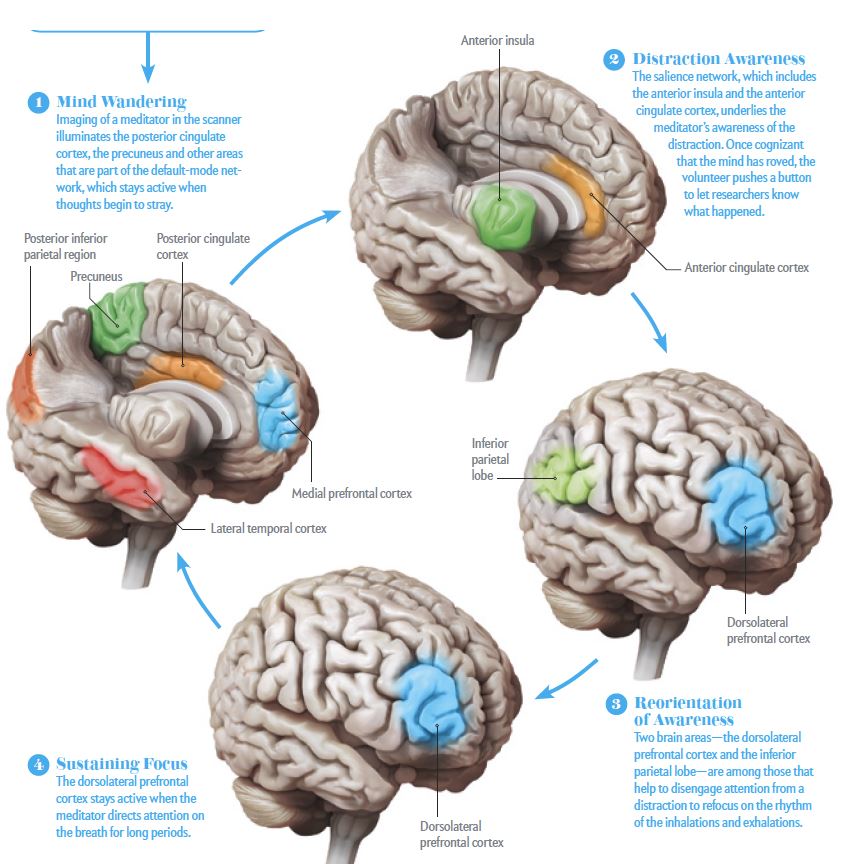

And in the act of meditation itself. We’re essentially practicing letting go all the time. We try focusing on the breath in our practice. You sit and you feel your breath coming in, and you feel it going out. And you take another breath. And another. But before you know it, even though you’ve continued to breathe, you’re actually thinking about getting plane tickets for a trip you need to take in a month. Or your son’s soccer game. Or your portfolio or bank account balance. And then you recognize that you’ve lost the breath. So, what do you do? You redirect your attention to the breath. You come back. And by doing that you’ve let go of whatever thought was worrying you. In the moment that you came back to the breath you’ve practiced letting go of worry. And then you’re with the breath again. A few moments later, you realize you’ve been fantasizing. Maybe having a fantasy of delicious food, or sex, or an exotic city. You’ve lost the breath again. So you come back to the breath. And what that means is that in that moment, you’ve practiced letting go of desire. In your meditation you are constantly practicing letting go of these mental states of desire, aversion, and delusion, just through the simple fact of being in the here and now with your breath. In the process you are transforming how you relate to yourself and the world. You are letting go of your unconscious habits and making the conscious choice of being here.

When you’re on retreat and you’re practicing intensively, you might begin to discover that your body’s in a lot of pain. Maybe you discover parts of the body that are wounded that you didn’t realize were wounded. And eventually you learn to meditate with the pain. You figure out how to do it. You’ve let go of the idea that your meditation practice has to be pain free. And to learn how to be with discomfort and pain in the body, also conditions us to be with discomfort with other things, with people, relationships, situations in our lives. So we learn about discomfort. And we learn about how to respond to discomfort rather than react to it. We cultivate wisdom just by making the conscious choice to return to the breath.

In our meditation practice we also learn to let go of the stories we tell ourselves about self/others: Our heads are full of such stories, and we see this when we practice. And we learn to let go of these stories. We practice this again and again. And eventually something becomes free in us, we don’t believe our stories so rigidly. And we realize that our thoughts are just events in consciousness, not facts. Like passing clouds.

Our practice helps us let go of emotions. It doesn’t help us get rid of our emotions. Rather the act of mindful awareness helps us metabolize our emotions so that we are able to let them pass through us and learn what we need to learn from them.

Our practice also helps us let go of the need to be in control. One of the most common delusions in life is the idea that we can control external events. It’s true that we can control some events, but most events big or small are beyond our control. And letting go of the need for that control is a great relief.

Part of what we want to control is the idea of perfection – that we can somehow become perfect. Which means that we are always seeing ourselves as a project – as somehow tweakable enough to attain an immutable state of excellence. Again there’s a tremendous relief when we can let go of this delusion.

And letting go of being perfect has a lot to do with the idea that we are a fixed and separate self in the first place. Mindfulness practice, especially when it gets deep, shows us clearly that human experience is in a constant state of impermanence and flow, and that if we can let go of the idea of being a solid “thing” and align ourselves with that flow, what we can become and be is boundless.

To let go is to admit that what we’re letting go of is not the source of a permanent happiness. It should be said that letting go is not about getting rid of something. Pushing something away aversively is just another form of clinging. Letting go is simply the habit of clinging starting to relax and fall away.

Is letting go an act of will? More often than not, letting go is not willed, you don’t do it, it does you. It arises naturally in the course of a daily practice. In fact, if we try forcing ourselves to let go it won’t work. We need to live through the experience, not avoid it, and letting go happens naturally as a result of being awake with that experience. We find the grace to let go because we’ve been willing to open our hearts to holding on. If we’re not willing to hold on, to make ourselves vulnerable by exposing our hopes and fears, we won’t learn how to become free.

How is it that letting go happens naturally? It’s because there’s something in each of us which wants freedom and recognizes it.

You probably know the feeling. It’s after lunch and the day seems to drag on and on. Your energy level is low, and you can’t concentrate on your work. You aren’t getting anything done, and there doesn’t seem to be anything you can do about it. You feel like taking a nap, but of course that’s not possible at the office. The afternoon doldrums are a well-known challenge to the work day, with some 28% of employees reporting falling asleep or getting very sleepy at work, according to the National Sleep Foundation. But there are ways of working with this listlessness. Here are five ways to manage your energy during the afternoon:

You probably know the feeling. It’s after lunch and the day seems to drag on and on. Your energy level is low, and you can’t concentrate on your work. You aren’t getting anything done, and there doesn’t seem to be anything you can do about it. You feel like taking a nap, but of course that’s not possible at the office. The afternoon doldrums are a well-known challenge to the work day, with some 28% of employees reporting falling asleep or getting very sleepy at work, according to the National Sleep Foundation. But there are ways of working with this listlessness. Here are five ways to manage your energy during the afternoon:

There is a trend towards minimalism in the dissemination of mindfulness. One does not really need practice mindfulness in an intensive way, we are told. We can do it in small digestible chunks. Some people suggest just 60 seconds of mindfulness practice. Or even one second. There are some that even suggest that formal practice periods are not needed at all – since we are already mindful now and then, the trick is to simply remember to be aware of what we are doing during our regular activities. If we could only remember to be aware more frequently, voila’ – we would be more mindful! I was struck by the following quote from a recent piece in the Harvard Business Review:

There is a trend towards minimalism in the dissemination of mindfulness. One does not really need practice mindfulness in an intensive way, we are told. We can do it in small digestible chunks. Some people suggest just 60 seconds of mindfulness practice. Or even one second. There are some that even suggest that formal practice periods are not needed at all – since we are already mindful now and then, the trick is to simply remember to be aware of what we are doing during our regular activities. If we could only remember to be aware more frequently, voila’ – we would be more mindful! I was struck by the following quote from a recent piece in the Harvard Business Review: