There are two primary modes of living: being and doing. The default way we act in the world is in the doing mode. This is the mode of getting things done, of planning, thinking, figuring out, meeting people and communicating, as well as knocking off items on our to-do lists. When we get busy “doing” things, there’s a little hit of pleasure that enters the brain. That’s actually a neurological reality. In fact, it can be quite addictive to be busy. There is also something about the way we’re wired that makes us more likely to engage in incessant activity. Through deep neurological conditioning, our brains tend to focus on threats – in modern life, instead of those threats being about the possibility of getting eaten by the local woolly mammoth, they’ll be more about surviving in the workplace, making a living, succeeding in the world, feeling safe and on top of things. The crazy busyness of modern life ensures that we are highly likely to operate in the doing mode most of the time. But the doing mode is also stressful and anxiety-filled. Adrenaline and desire are its main fuels. When people operate in the doing mode all the time – even to the point of “doing” their leisure activities – stress can become chronic. And when stress becomes chronic, life becomes very difficult, for a whole host of reasons, including the diminishing of personal effectiveness as well as health problems. Personal happiness is the greatest casualty when stress hijacks our lives.

The doing mode is about effort, striving, managing threats or opportunities through our strengths and weaknesses. The being mode is completely different. When we are in a state of being, there is no need to accomplish anything, no need to be the best at something, no need to strive or figure things out. We are simply allowing ourselves to be. Just as we are. With all of our simple and profound aliveness, with our emotions, thoughts, body sensations, and our precious breath. The being mode is about stopping the treadmill of busyness and simply letting ourselves be alive. When we do this kind of stopping, mental activity doesn’t stop — mental activity continues but, since we are no longer fueling it with the actions of doing, our mental patterns tend to clarify and unwind. This clarifying in our minds helps us see more clearly what is needed with our challenges. Stopping also helps us let go of striving to be anything and rest, refresh, and recharge ourselves. This relaxes the nervous system, bringing greater ease and peace to the body. Stopping and letting ourselves be also puts us in touch with what’s happening in the body – we notice pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral sensations. We are sensitive to joy and sorrow, and we are tuned in to intuition and creative breakthroughs.

Our default actions come from the doing mode – the habitual monkey-mindedness of human life. But our wisest actions come from the being mode. The place of stopping, of honesty, clarity, and stillness. However, it would be a mistake to think that being and doing are mutually exclusive states. Both are important. Both are connected. But since we tend to overvalue doing and ignore being, even a little bit more being in our lives will make us happier and healthier. With more being time in our lives our actions will be more influenced by stillness and wisdom rather than the autopilot reactions of the doing mode. So a regular daily dose of being is what’s needed. Perhaps that means lying in a sauna for a half hour, going for a walk, or sitting in a chair and focusing on your breath. Whatever you do, give yourself the gift of your own being. You deserve it.

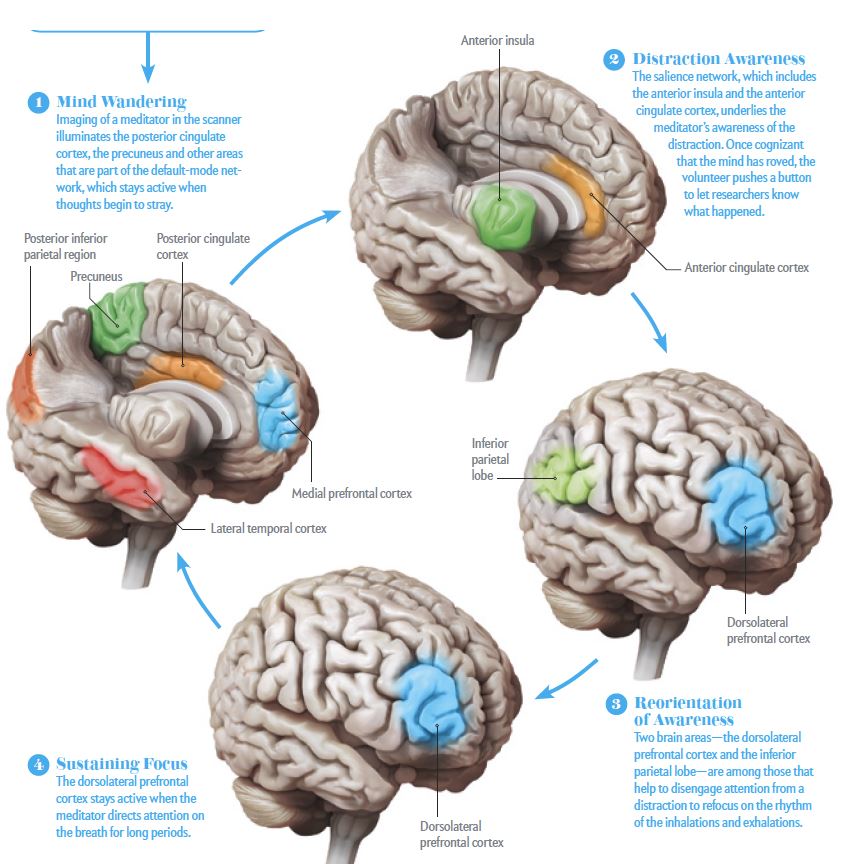

If you practice mindfulness meditation, you’ve had this experience: you are focusing on your breath, one inhale and exhale at a time, when suddenly a compelling thought arises, distracting you. Maybe the thought is about work, or a relationship, or the vacation that starts next week, or whatever. That thought then leads you down a series of mental rabbit holes until – five minutes in – you realize that you’ve completely lost the breath. It can be humbling to realize how little control we have over our minds. Those thoughts are so compelling!

If you practice mindfulness meditation, you’ve had this experience: you are focusing on your breath, one inhale and exhale at a time, when suddenly a compelling thought arises, distracting you. Maybe the thought is about work, or a relationship, or the vacation that starts next week, or whatever. That thought then leads you down a series of mental rabbit holes until – five minutes in – you realize that you’ve completely lost the breath. It can be humbling to realize how little control we have over our minds. Those thoughts are so compelling!

Many meditation teachers say that there is no wrong way to meditate. That showing up and doing the practice is what’s important. Having said that, the following list of common mistakes or misconceptions about meditation keep showing up in my teaching with students. They are:

Many meditation teachers say that there is no wrong way to meditate. That showing up and doing the practice is what’s important. Having said that, the following list of common mistakes or misconceptions about meditation keep showing up in my teaching with students. They are: