Mindfulness has been associated with so many positive things – greater focus, clarity, joy, compassion, emotional balance, resilience, general well-being, and decreased stress, to name just a few – that it’s easy to ignore one of its primary purposes. Mindfulness is essentially a practice of moving towards suffering, of coming into relationship with the challenges, traumas, anxieties and stresses, both large and small, of our lives. Because suffering is an unavoidable fact for every human being, the way we relate to it is critically important.

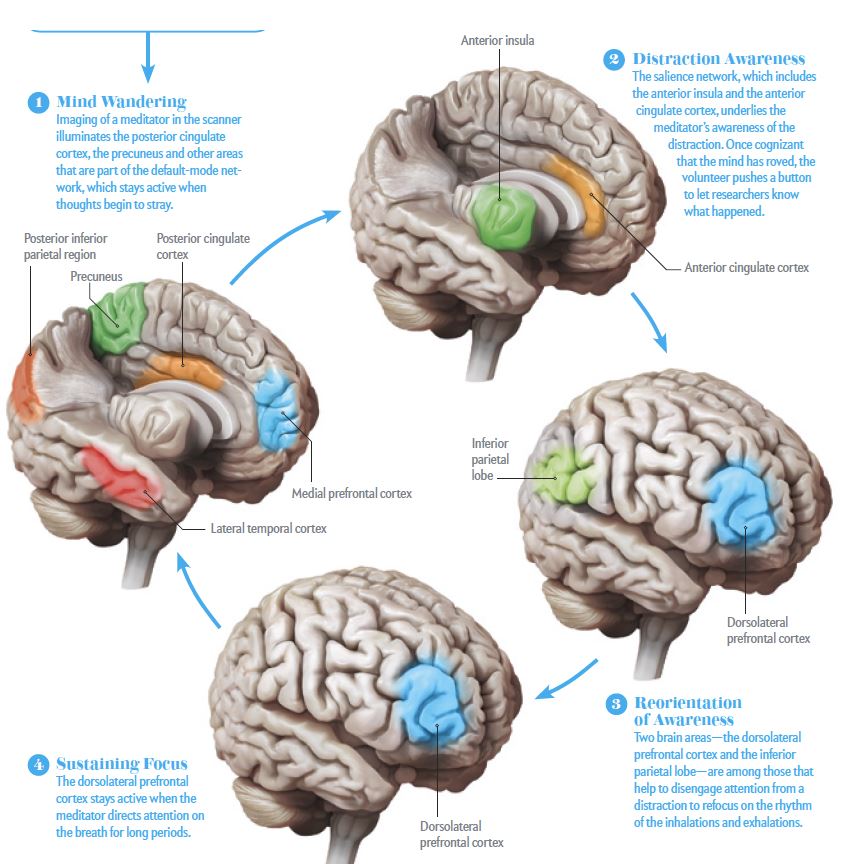

The moment we sit down to meditate, we force ourselves to be aware of the thoughts, stories, and emotional patterns that drive us most of the time. Many of these patterns are habitual, unconscious, obsessive, and negative. Yet they set the tone for how we respond to events. When we sit down to meditate, we also become aware of the places in the body that are tight, registering tension, or wounded. Because we are so driven by our to-do lists, our non-stop busyness makes it easy to avoid our difficulties, and to avoid our bodies and the stress signals they give us. But that avoidance conditions us to think that our difficulties are mistakes – rather than something we can be in relationship to.

Mindfulness teaches us that rather than avoiding suffering, we need to move toward it, with openness, courage, and curiosity. We become intimate with our suffering not to fix it or change it but to know it fully, to see how it effects our life. When we hang out with our fears, wounds and anxieties without needing to fix them, we bring their energy into consciousness in a way that brings us healing. We clearly see the effect that our habitual thoughts and emotional patterns have on us. We see the suffering that our minds continually create, and we see the tension and stress in our bodies as a form of that suffering. When we see these patterns over and over again through daily meditation, over weeks, months, and years, our perspective changes. Rather then believing our stories, we see that they are just mental events that don’t have to control us.

As a result of this regular intimacy with our pain, we become more whole as a result, and more free. And we start to think and act in ways that reflect that wholeness. You may not learn this in the next magazine article on mindfulness you read – but it takes courage to be mindful. Because facing our suffering is quite challenging, and also quite necessary for a fully lived life.

I recently returned from a 9-day intensive meditation retreat focused on the practices of concentration and mindfulness. The first four days of the retreat presented me with the usual struggle – re-learning how to slow down, quitting caffeine, abandoning cell phones, blogs and the internet, and mostly, just watching the habit patterns of my mind replay themselves ad nauseum. By day five I was really settling in nicely, my mind was calmer, clearer, and more focused, and I was able to steady my attention on the breath – and even more interestingly to me – the stillness of knowing the breath. I was really beginning to hit my stride and was looking forward to deepening my concentration in the following final days of the retreat. But on Sunday night, instead of listening to that night’s talk on practice with my fellow practitioners, I found myself in the emergency room of the nearest hospital with an IV drip of saline in my arm.

I recently returned from a 9-day intensive meditation retreat focused on the practices of concentration and mindfulness. The first four days of the retreat presented me with the usual struggle – re-learning how to slow down, quitting caffeine, abandoning cell phones, blogs and the internet, and mostly, just watching the habit patterns of my mind replay themselves ad nauseum. By day five I was really settling in nicely, my mind was calmer, clearer, and more focused, and I was able to steady my attention on the breath – and even more interestingly to me – the stillness of knowing the breath. I was really beginning to hit my stride and was looking forward to deepening my concentration in the following final days of the retreat. But on Sunday night, instead of listening to that night’s talk on practice with my fellow practitioners, I found myself in the emergency room of the nearest hospital with an IV drip of saline in my arm.

The human mind is beautiful, but also dangerous. Our thoughts and emotions can be powerful drivers of our behavior. Since many of our mind-states are negative, our actions are often at the mercy of our thoughts. Gloomy and pessimistic thinking, long established from habit, creates rigid and stereotyped narratives psychologists have labeled cognitive distortions. You probably know some of these stories from your own experience. They often begin with, “I’ll never be good at this because,” or “I’ll never be loved because,” or “My pain will always be like this because,” etc. These stories become so familiar to us that they define who we think we are or can become. And the actions we take in the world reflect the limitations of this thinking.

The human mind is beautiful, but also dangerous. Our thoughts and emotions can be powerful drivers of our behavior. Since many of our mind-states are negative, our actions are often at the mercy of our thoughts. Gloomy and pessimistic thinking, long established from habit, creates rigid and stereotyped narratives psychologists have labeled cognitive distortions. You probably know some of these stories from your own experience. They often begin with, “I’ll never be good at this because,” or “I’ll never be loved because,” or “My pain will always be like this because,” etc. These stories become so familiar to us that they define who we think we are or can become. And the actions we take in the world reflect the limitations of this thinking.