The word resistance has been getting a lot of attention lately, in light of the U. S. presidential election and its aftermath. Resistance is actually a necessary way of being engaged, both politically and in other ways. But if there is something we dislike or feel is unjust that we feel compelled to resist, how can we practice that resistance in a wise way?

Resistance can take many forms. Resistance as it unfolds in big events like marches. And also the way resistance plays itself out among people we know, our friends and family, and colleagues. The types of messages we see on social media. The retweets, the status updates, the links to insightful articles about…how to resist.

During the last few months I’ve also observed my own tendencies around resistance. I watched my state of my mind in the days after an election whose outcome was not what I expected. I noticed the cortisol levels starting to impact my body as soon as I’d wake up in the mornings and remember the election and groan in anguish.

But how does resistance look through the lens of mindfulness? How can we practice wise, non-reactive resistance? Of course, the very question implies that there are forms of resistance which are not wise – or not as wise. What follows are some thoughts.

I’ll start by citing a very famous quote from the Buddha:

“Hatred does not cease by hatred, but only by love; this is the eternal rule.”

And one of the most notable things I’ve observed about how I experience resistance in myself and others is the tendency to indulge in hatred. Hatred is kind of like the mind’s way of having clarity in a difficult situation. Have you ever noticed that? That when you hate something or someone, there’s a certain cutting to the chase power? Or maybe hatred is a way of feeling in control…or a way of defeating our fears.

So this is one major way that resistance plays itself out. People get angry and they project that anger outward. There’s a lot of projecting of anger in our politics…anger placed on politicians, on people in Congress, on our friends or relatives who maybe voted differently than we did. A horrible law gets passed or an executive order gets signed, and people are up in arms with understandable outrage.

But the problem with all this hatred and ill will – which I’ve certainly expressed many times myself over the years – is that, as the Buddha said, hatred does not cease by hatred. But only through love. If you are an activist, or even not, that is a very challenging point of view to take on.

So hatred does not end other forms of hatred, it just leads to more hatred. And yet we are compelled to act against what we believe is not just. This is what activism is all about. But activism is kind of based on righteous indignation, isn’t it? On the left and the right. And there’s the paradox. And the proposition that I’m going to make is this – that political activism will burn itself out when its primary driver is hatred. Hatred is not sustainable. And yet it seems to drive so much in our politics and culture wars.

Lately I’ve been speaking with my fellow teachers and we came up with something that I think is quite simple and quite wise which may be helpful…especially in our current moment.

So much of how we mobilize our resistance is around what we don’t want, what we hate, what we’re against. But the question my colleagues and I were recently discussing was, what would happen if instead of focusing on what we’re against, we focused on what we’re for? What do we believe in, what do we value? And how do we express those values? If we could engage in protest about what we’re for, would we need to have an enemy to mobilize us?

I’m reminded of the teaching of the two arrows here. We experience pain. That’s the first arrow. Then we have a mental reaction to the pain which often makes the pain worse. That’s the second arrow.

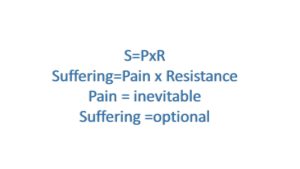

And this two arrows teaching is expressed beautifully in a kind of a modern teaching paradigm that’s sometimes used in coaching, organizational consulting, and so on. Which goes like this: Suffering equals pain times resistance (S=PxR). And the idea is that pain is a part of life, and suffering is what we add to pain through our mental reactions. And usually that has to do with our resistance to the pain.

And so the idea from an activism perspective is that the more we can be with the pain of events consciously – in other words, the less we resist the pain of political events internally – then the wiser our external response will be. Thus the more effective our resistance becomes because we won’t be eating ourselves up with hatred.

To put it another way, when we learn not to resist our pain internally, it may help us resist externally with greater effectiveness and more sustainably.

So for me there are two kinds of resistance.

There’s resistance with aversion – focusing on everything you’re against, using hatred as a motivator; and there’s resistance with love or non-hatred, focusing on your values and what you stand for as a motivator.

So I propose that when we resist with love, we’re more oriented to focusing on what we’re for rather than what we’re against. We’re not focused on having and demonizing an enemy. We’re focused on justice. We know what’s causing suffering and we act with fierce compassion…but not with hatred. Because we are motivated by love and what we value, we live to fight another day, month, and year.

In meditation, when things don’t go our way, we tend to resist. Feeling restless? Then fidget incessantly as a way of not feeling the restlessness or what may be behind it. Have a hard time focusing on your breath? Then berate yourself as a bad meditator and despair at ever getting “good” at the practice.

In meditation, when things don’t go our way, we tend to resist. Feeling restless? Then fidget incessantly as a way of not feeling the restlessness or what may be behind it. Have a hard time focusing on your breath? Then berate yourself as a bad meditator and despair at ever getting “good” at the practice.