Really a very nice honor. And I’ll be posting more soon.

Author Archives: Bill Scheinman

How Mindfulness Helps Us Communicate

We are in communication with people all the time. We have conversations with colleagues at work, with our mechanic, with our spouses and kids, and we convey messages both verbally and non-verbally. But how often are we really being present while communicating? Because relationships can be stressful, it’s important to bring mindful awareness to the domain of communication.

We are in communication with people all the time. We have conversations with colleagues at work, with our mechanic, with our spouses and kids, and we convey messages both verbally and non-verbally. But how often are we really being present while communicating? Because relationships can be stressful, it’s important to bring mindful awareness to the domain of communication.

Mindfulness helps us cultivate an assertive communication style rather than an aggressive or passive one. Tuning in to mind-body experiences while communicating helps us understand how someone’s words are landing for us; by acknowledging hurt or worry or fear, we create a space that helps us respond wisely rather than rashly.

Practicing empathetic listening is also a great way of establishing clarity and trust in dialog. When we let go of our agendas, we can open to what people are saying and really understand them. When someone feels deeply heard and understood, conflicts lessen and collaborations are more effective.

Here are some suggestions for maintaining mindful awareness during conversation.

While speaking:

-Stay in touch with your body to connect with your own authenticity. When we speak words from a place of body awareness, it’s easier to know when we might be going astray or uttering thoughts or ideas that are not in alignment with our values

-Speak truthfully. Dishonest speech leads to problems down the line that may be hard to fix. When people know they can rely on us to be truthful, it goes a long way to establishing a sense of trust.

-Speak beneficially. If what we speak is without benefit to the person we are communicating with, why do we need to say it?

-Speak with kindness. Not only is speaking with kindness more relaxing and peaceful, but people tend to respond to kind words rather than harsh ones. Keep in mind, speaking with kindness does not mean that you neglect constructive criticism when it’s appropriate. We can criticize, set boundaries, confront, and be kind while doing it.

-Speak at the right time. If you give feedback to someone who is visibly upset, it may not be the right time to do so. Being sensitive to the when of speaking supports effective communication.

While listening:

-Stay in touch with your body to notice how the words land for you. If someone says something unfair, it’s better to feel how those words land in your body first – it gives you the appropriate pause and a chance to release any negative emotions that might have been triggered by the words. When you do speak, you’ll do it with more presence and non-reactivity.

-Practice empathetic listening by understanding that everyone wants to be fully heard. While advice may be useful, it’s helpful to realize that much of the time when people are struggling they really don’t need advice – they need to be heard.

-Have an open mind towards the speaker even if you know the person well.

-Return your attention to the speaker when your mind wanders.

Desiring the Now

If you practice mindfulness meditation, one thing you’ve noticed is how easy it is to get distracted. Our minds are so busy! If you’ve looked a little more closely at the nature of your distractions, you’ve probably noticed the central role that desire plays. How often have you noticed that your thoughts have moved into the realm of fantasy? When you find yourself wanting some wonderful outcome that has not yet happened, that may never happen, whether that wonderful outcome is a new job in a new city, or a windfall on an investment, or a new lover, or a new set of cool friends, or a new body, home, car, or whatever it may be. Or maybe your desire takes an aversive form – you are feeling frustrated with the meditation, you’d rather be somewhere else, doing something else, something productive, like ticking off the items on your to-do list. Or feelings come up that you’d rather not feel – physical pain, emotional pain, stress, anxiety, panic, rage. Why don’t these things just go away! You desire them to be gone.

When we desire something, it usually means that what we desire is not what is here. It’s some future or potential experience that could happen, but it’s not happening now. Now the problem with desiring something which is not here is that the desire is pointing us away from the present moment, which is – as many people have said – the only actual moment that ever is. The present moment is actually the moment in which our lives are capable of being lived. If we live in any other moment than the present moment we are not living our lives. That also means that we are not capable of making wise choices about how to respond to our daily challenges. And when we live in a moment other than the present one, intimacy in any relationship is not possible.

Desire shows up a lot in mindfulness practice. And mindfulness masters over the centuries have taught a variety of ways of working with desire when it arises. One of the most powerful ways of approaching desire is to simply acknowledge it without judging it. This is easier said than done. Many people (yours truly included) have a tendency of thinking that we need to get rid of our desires in order to practice mindfulness, in order to be “good meditators.” Desire is so messy and what we need is to calm things down, we think. This aversion to desire, to coin a phrase, assumes that desire in the context of meditation is a mistake, something that needs to be gotten rid of, purified, expunged. Unfortunately, trying to get rid of our desires doesn’t work.

It is far more powerful to acknowledge that the mind is filled with desire, perhaps with a light mental note, like wanting, wanting. And, crucially, to recognize that desire is present but without making any judgments about yourself. Desire is simply present in the mind. It doesn’t mean you are a bad mindfulness practitioner. Simply noticing the desire, even if you have to do it a hundred times in five minutes, and then returning to your breath or whatever object of focus you are using, is a powerful way of freeing yourself of the desire. By acknowledging the presence of desire as a routine mental event, then releasing it gently (without judgment) and returning to the object, you are conditioning yourself to dis-identify from the desire. You are in effect training yourself not to be ruled by your desires. Over weeks, months, and years of experience, I have found this to be a powerful tool in my own practice.

But what would happen if we could take the powerful energy of desire and apply it to the present moment? What if we were able to desire what was happening right now? And what would desiring the present moment look like anyway? It should be said that according to the classical understanding of mindfulness, there are two types of desire. One is the desire for things not in the present moment, the desire we’ve been exploring here. This sort of desire is associated more a sense of thirst, of never having enough, of inner deficiency. The second desire is something else. Rather than thirst, its characteristic is more aspirational. It’s considered wholesome desire. The desire for love, happiness, connection, good work, freedom, are all examples.

So what would it mean to desire the now? For one thing, desiring the now can be thought of as a practice, not just an idea. Desiring the now means welcoming what is here, in any moment. That means welcoming even something that is unpleasant. Welcoming means meeting whatever it is with our full attention, presence, resources, and wisdom. Whenever you forget to welcome what’s here, you simply come back to what’s here. It’s just like coming back to the breath. Desiring the now also means letting go of our fixed ideas about things. It means looking at each person and each moment with fresh eyes, free of cognitive rigidity and bias. Whenever your old ideas yank you back into autopilot, you can recognize that and return to the now, to the fresh aliveness of beginner’s mind. Above all, desiring the now means allowing yourself to become intimate with life. Interestingly enough, intimacy for me is a lot less about knowing someone or something and much more about not knowing them. To be intimate means to be open to the mystery of everything we’re doing. The human being you are speaking to may be a work colleague you’ve known for years. There are things about this person you can say you “know.” But on another level, your colleague is an absolute mystery. There is so much you don’t know about this person. In fact, there is so much we don’t know even about ourselves. Desiring the now means being open to discovering what the mystery of life is, moment by moment, as it unfolds.

Basic Training

When we say we practice mindfulness, we’re really talking about training. It’s just like going to the gym.

When we start on the treadmill at the gym, in the beginning we can only do 10 or 20 minutes. But if we keep doing that 20 minutes we’ll find that eventually we’ll be able to do 30 minutes, then 40. Our body responds to the steady routine of the treadmill by developing more stamina. Or when we start lifting weights, we may only be able to lift 10-pound dumbbells. Then our muscles get stronger and we can lift 20-pound dumbbells, then 30. The steady, consistent training in weight lifting expands the capacity of our muscles to lift heavier weights.

Mindfulness is the same way. When we’re trying to be mindful of the breath, at first we can only keep the mind on the breath for a few moments at a time. The breath is like a marble that keeps bouncing away from us: we keep having to chase it. But if we keep training ourselves to be with the breath, to be mindful, we discover that we can stay with the breath for longer periods and when we do lose it we come back to it sooner. Also, when we meditate on the breath on a regular basis we begin to notice that the gaps of time when we are not being present are of shorter duration.

So in the gym we build up our muscles day by day. Then one day a friend asks you to help her move a couch, and you can do it because you’ve got the strength. You’ve been training. The same is true with meditation. When we face difficulty in meditation, we’re learning how to face difficulty in our lives. If you learn how to be with the breath when it’s feeling tight, or to be with the body when there’s pain, or to be with difficult emotions, you’re doing the heavy lifting of your life — you’re training yourself to engage your challenges in a healthy and responsive way. If you become annoyed by a train of thought during meditation, the annoyance is the same as when you get irked by something your boss says. The difference is that in meditation you have a chance to work with the annoyance without getting lost in acting on the annoyance — like getting into an argument with your boss.

It all comes down to meeting our suffering just as it is. Sitting and breathing while you have a stabbing pain in your shoulder, or a maddening itch on your nose, or a feeling of loneliness and loss in your belly — staying with these things without trying to fix them opens our hearts and minds in ways they wouldn’t open if we avoided them. If we scratched that itch or ate some chocolate instead of allowing ourselves to feel lonely, we would lose the opportunity to train ourselves to face our suffering. One thing about suffering: we can’t cure it by avoiding it. If we avoid it, it usually gets worse. Or else it goes underground, which then causes stress. Mindfulness teaches us that we can transform our suffering not by avoiding it but by moving toward it and meeting it with presence, honesty, and openheartedness. If we can find our ground in the midst of our anguish, something eventually happens to the anguish: it expends its negative charge and transforms into a teaching about our life.

When soldiers first enter the Army they go to basic training. With mindfulness, basic training is also advanced training. You never outgrow the need for learning the basics. To be present for things just as they are, to open our hearts to what is difficult, is actually quite courageous. For this reason you could say that just like a soldier in training, you need to have a warrior spirit to really be mindful. And you also need the discipline to stay at it day after day.

Angry Political Speech Got You Down? Try Kindness Practice.

The regions of the brain that control emotions are much older than those regions that regulate rational thought and executive functioning. The function of emotions when we were evolving was to help us manage threats to our survival. The emotion of disgust, for example, originated as a means to avoid bad food or a bad smell.

But the complexity of modern life makes the experience of emotions far more complex than it was a million years ago. To quote Daniel Goleman, “While in the ancient past a hair-trigger anger may have offered a crucial edge of survival, the availability of automatic weaponry to thirteen-year-olds has made it too often a disastrous reaction.”

Because our emotions are so powerful, they can get control of our rational minds rather easily. Even if we might like to see ourselves as emotionally positive, as kindhearted and compassionate people, a sudden emotional spike can ruin all our good intentions in a moment of anger.

Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in the realm of politics. Politics is one of those things that can really rattle us emotionally. Politics in the United States has always been a contact sport, but over the last few decades, as many people have observed, the political landscape has become increasingly polarized. It seems like people identify with their values so strongly that they find themselves hating others who have different values. We admire political figures who represent how we feel about the world, but often demonize political figures who hold views we dislike. We find ourselves avoiding people who hold different political views than us, unless they’re family, of course – in which case we do our best not to argue at Thanksgiving.

Perhaps the tribalization of media is to blame for the tendency many people have today to visit only the newspapers, websites, Facebook pages or Twitter feeds that validate their view of the world. But for whatever reason, politics can really get our blood boiling.

In 2016, the current political season seems to have hit new lows for negativity, anger, vilification, blaming, disgust, and overall nastiness. So much negative information gets disseminated in the form of campaign ads, flyers, media coverage, speeches, demonstrations, and debates, that it’s a wonder that our psyches aren’t overwhelmed by the toxic atmosphere. This is especially true for political junkies, who feed off the news during political season the way a vacationer eats rich food.

If you are one of the people who is feeling emotionally exhausted by today’s politics, a simple practice of cultivating kindness can be a big help. Both the ancient practices of mindfulness and kindness meditation and modern research point to an amazing fact: deliberately cultivating kindness, friendliness and compassion is not only possible, it’s good for your health and sense of well-being. Research findings have shown that practicing kindness can decrease blood pressure, that it reduces inflammation and delays aging, that it enhances the immune system for both the giver of kindness and the recipient, that it improves our relationships, and makes us overall happier. And the amazing thing about us human beings is that our brains are trainable. We can develop kindness like we can any other skill.

The first step in a kindness practice is altering your perspective a little bit by considering a simple yet irrefutable fact: every human being wants to be happy, and no one wants to suffer. This is a radical understanding of the human condition that is very helpful when we find ourselves hating or feeling disgust for others. This basic desire for happiness and dislike of suffering is true even in the case of someone whose behavior is malevolent or in some way deplorable. Even people who do bad things want to be happy; the bad things they do, they are doing out of a misunderstanding of what will make them happy. Another way of shifting perspective on people we dislike, is to consider this idea: how much better off the world would be if all of its difficult people were happy.

Once these perspectives are in place, the next step in a kindness practice is to set your intention to cultivate kindness within yourself. One of the most effective ways of doing this is to repeat to yourself phrases of kindness and well-wishing. The ancient Buddhist practice of metta, often translated as lovingkindness, which the man known as the Buddha recommended to his followers 2,600 years ago, uses a series of simple phrases which set the intention for kindness and also recognizes the need of others to be happy. A simple version of these phrases are:

May I be safe

May I be healthy

May I be happy

May my life be filled with ease and well-being

You can certainly modify these phrases and use your own words to make them align with what resonates for you. In doing this practice, start with yourself. Sit comfortably in a chair or on a cushion, and repeat these phrases of well-wishing for yourself in silence, over and over again. Don’t worry about the outcome. Focus on the repeating of each phrase. Each time you repeat the phrases, you are basically repeating your intention to be happy. Do this for a few minutes, then repeat these phrases for a good friend for the same amount of time. Like so:

May [friend’s name] be safe

May …be healthy

May …be happy

May …life be filled with ease and well-being

Then repeat the phrases for a neutral person in your life. Like so:

May [neutral person’s name or description] be safe

May …be healthy

May …be happy

May …life be filled with ease and well-being

And then for an enemy or difficult person, including a political figure that you dislike. Keep in mind that when you say the phrases for the person you dislike, the goal is not to like that person. The goal is to recognize your common desire for happiness, and in some way to unfreeze your heart.

May [political figure or enemy] be safe

May …be healthy

May …be happy

May …life be filled with ease and well-being

Finally, you can say these phrases for all beings everywhere.

As you spend time doing this practice, you may feel strong heart-opening emotions when you say these phrases to yourself. If that happens, just welcome them, and keep opening to that experience by repeating the phrases. If nothing seems to be happening, or you feel numb, that’s perfectly fine, too. The phrases of well-wishing are like seeds that are planted and they’ll sprout in their own good time.

Sometimes kindness practice brings up the opposite emotions. So if you experience anger or grief, extend kindness to yourself and to those emotions that you’re having and don’t judge them. Remember this: to practice kindness is to be present with whatever blocks kindness. Above all, keep saying the phrases, acknowledging whatever else is arising without any judgment at all.

And the next time you find yourself getting upset by something in the political realm, it may be a bit easier to come back to a sense of emotional balance and an even-handed perspective.

A Simple Practice for Hitting the Reset Button

You’re sitting at your desk at work when you realize that you feel disconnected from yourself, you feel anxious and tense, and your mind is full of half-formed thoughts. You seem to have lost your presence of mind, your inner equilibrium thrown off.

At such times, a simple exercise in awareness can totally shift the energy and change your perspective. The Mindful Reset can take as long as 10 seconds or one minute to do.

Firstly, when you notice that you’re feeling out of sorts, simply stop what you’re doing, close your eyes if you can, and notice your breathing. Follow the breath as it comes in, and follow it as it goes out. Notice what the breath feels like. Is it relaxed and easy from the beginning to the end? Is your breathing tight or squeezed? Noticing how the breath is also helps you notice if there are any sensations of tension or tightness in the body. Follow the breath as it travels through your body to become aware of any sensations of discomfort or contraction that are making themselves known. Notice wherever the body feels tight or tense; acknowledge those sensations without needing to get rid of them. You can invite those parts of the body to relax, but do it softly, not as a command but as a kind request. Simply bringing awareness to how your breathing and body are can begin to relax them.

Secondly, notice what your state of mind is like. What thoughts are present? Are they thoughts of the future or the past? Are they thoughts of worry, planning, remembering, judging, figuring out? Is your mind clear, collected, unified? Or is it dull, muddy, scattered? Just notice what’s going on in your mind without any judgment or self criticism. Again, simply bringing awareness to how your mind is and what thoughts might be present gives you important information about what is driving your behavior right now. When you are aware of what patterns are present in the mind, you are less likely to be controlled by them.

Thirdly, notice what the emotional tone is like in your experience. Underneath those physical sensations and thoughts, what emotions might be present? Is there worry, fear, sadness, anger, anxiety, doubt, frustration? Again, don’t feel like you need to get rid of the emotions. Just noticing the emotional tone of any experience gives you greater freedom in responding wisely.

When you give yourself the space to notice how you are, your mind starts making adjustments that will bring you back to equilibrium. This is called a closed feedback loop. The system of mind-body is working to bring you back into balance.

You can do the Mindful Reset at any time. While at your work space, before entering a meeting, while walking to lunch, or while driving your car (with your eyes opened, of course!).

The Mindful Reset doesn’t magically solve all your problems or remove all your pain. What it does do is put you in touch with yourself from the non-judgmental perspective of awareness. Without this perspective, we contract and tense up when faced with a challenge. We are under the control of the reactive mind. With the non-judgmental perspective of awareness, we release, let go, and see the big picture. We are being guided by the responsive mind. Mindfulness returns us to the clear-headed perspective from which it is easier to see how to meet our challenges and live our lives with more wisdom and balance.

Awareness is Not What it Knows

Awareness is one of the most miraculous things about being alive. Scratch that. It is THE most miraculous. Without awareness, we would know nothing. We would not know the trees, the sky, the mountains, the stars, the eyes of our beloved, the laughter of children. Or love, fear, anger, or joy. And yet, what is this awareness? One of the insights that can arise when we spend intensive periods of time focusing on a simple meditation object like the breath is that the awareness which knows the breath is not itself composed of the breath. Likewise, our awareness of pain is not the pain itself; our awareness of our thoughts and emotions is not the content of those thoughts and emotions. Our awareness, in fact, is not what it knows. Nor is our awareness bound by the conditions of everyday life.

Nor can we shut awareness off. As long as we are alive and awake, awareness is present. Sit with your eyes closed for 30 seconds and try not being aware. You can’t do it. Another powerful thing about awareness is that as we develop our ability to focus and still our minds, our awareness can turn around and observe itself. As we learn to relax the habits of the egoic personality, the non-judgmental clarity of awareness starts informing our lives more and more. Instead of getting completely identified with the pleasant and unpleasant experiences which occupy our days, we are more likely able to step back and see them as passing events which we can relate to with more ease and wisdom. The more we align ourselves with the point of view of awareness, the more we can hold the joys and sorrows of our lives without getting swept away in knee jerk reactivity to them. This holding of our experience means that we are relating to our lives with more mental clarity and freedom and are less likely to experience suffering from the changeable, unsatisfactory, and selfless nature of events.

From a working perspective, aligning ourselves with awareness makes us better colleagues – we’re more present during conversations, and more likely to see our colleagues with fresh eyes. Awareness tells us when we’re in need of a break, when we’re losing our focus, or when we need to reset our work priorities. Awareness keeps us on track so that we can manage our time better, and it helps us stay present during long meetings. Awareness puts us in touch with our emotions so that, when responding to an upsetting email, we pause long enough to acknowledge how we’re feeling, defusing the raw emotions so that we can craft an appropriate response that isn’t coming from a place of anger. Awareness helps us see the unskillful habit patterns of our minds, dis-identifying from negative narratives that hold us back at work and socially.

One of the most amazing things about awareness is that it is not static. It is a living experience, something that we can keep opening and deepening the more we practice.

Is training the mind unnecessary for developing mindfulness?

There is a trend towards minimalism in the dissemination of mindfulness. One does not really need practice mindfulness in an intensive way, we are told. We can do it in small digestible chunks. Some people suggest just 60 seconds of mindfulness practice. Or even one second. There are some that even suggest that formal practice periods are not needed at all – since we are already mindful now and then, the trick is to simply remember to be aware of what we are doing during our regular activities. If we could only remember to be aware more frequently, voila’ – we would be more mindful! I was struck by the following quote from a recent piece in the Harvard Business Review:

There is a trend towards minimalism in the dissemination of mindfulness. One does not really need practice mindfulness in an intensive way, we are told. We can do it in small digestible chunks. Some people suggest just 60 seconds of mindfulness practice. Or even one second. There are some that even suggest that formal practice periods are not needed at all – since we are already mindful now and then, the trick is to simply remember to be aware of what we are doing during our regular activities. If we could only remember to be aware more frequently, voila’ – we would be more mindful! I was struck by the following quote from a recent piece in the Harvard Business Review:

“Many people also confuse mindfulness with meditation. Meditation is a tool to achieve mindfulness, but it requires a practice that some people find difficult. Mindfulness, as my colleagues and I study it, does not depend on meditation: it is the very simple process of noticing new things, which puts us in the present and makes us more sensitive to context and perspective. It is the essence of engagement.”*

While it is true that mindfulness and meditation are different things, our conditioning as human beings tends to make us grasp at shiny objects – in other words, our media-filled, to-do-list-driven lives make us distracted. And while mindfulness is theoretically possible at any moment when we tune in to the truth of our direct experience – the fact is that our conditions make it hard to do this without deliberate training. If you were going to help your friend move a heavy couch and you had a month to prepare, just thinking about moving the couch might not be enough. But going to the gym and lifting weights during that month will strengthen your muscles so that, on the day you need to move the couch, you will be strong enough to do so.

It’s the same with mindfulness training. When we practice formally we are conditioning our minds to be more alert during the non-meditative moments of our lives. Formal mind training makes it more likely that we’ll ‘notice new things.’ While intentional effort is necessary to cultivate mindfulness, the time commitment doesn’t have to be onerous. Even 10 minutes a day can make a huge difference. And sitting still doesn’t need to be your practice. It could be mindful walking or standing for 10 minutes. Even lying down for 10 minutes and doing a body scan could work. The key is to set aside a time each day just for your being.

*https://hbr.org/2016/01/mindfulness-isnt-much-harder-than-mindlessness

Survey Confirms: Almost Everyone Is Stressed Around the Holidays

I am extensively quoted in this article from Entrepreneur Magazine.

I am extensively quoted in this article from Entrepreneur Magazine.

Practice: Mindful Browsing

The holiday season certainly has its stresses. Big family gatherings, the planning of meals and events, traveling, while juggling work responsibilities at the same time, can all take their toll. One thing that can certainly cause discomfort is the pressure to consume – and the tendency within the stresses of the holidays to consume more than we need. One thing mindfulness practice can do is to make us aware of our habits – our habits of relating to stressful situations, people, the types of thoughts we like to indulge in, and our habits around consuming. Sometimes we consume things not because we need them but because of an urge. And sometimes that urge is based on deep-seated emotional tendencies that are often unconscious.

Here’s a practice I call mindful browsing that can help us pause and create more spaciousness in our experience of being consumers. It’s important to remember, though, that maintaining your daily meditation practice during the holidays is a vital support for a practice like this. When you do this practice, please don’t judge yourself. Just notice what your experience is in any given moment. Be curious about your patterns around consuming, but not self-critical. Hold it all with a kind awareness.

When shopping for food or other things, and you feel the urge to buy, try doing some mindful browsing. Take a period of time, from a minute to 10 minutes or whatever, and just look at what you are desiring without purchasing it. Just allow yourself to feel the sense of wanting – the hunger in your stomach, the desire for something fancy, the deliciousness of the food or the style points of the clothing, etc. Make a self-inquiry like this: Is this thing I am wanting going to make me happy? Also notice your intention: Is this thing I am wanting actually going to nourish me, or do I just want it out of habit? Am I just reacting out of a sense of restlessness, boredom, fear, anxiety? Allow your hunger for whatever it is to be held in awareness. After taking such a pause, you may discover that the desire for that thing has either changed or disappeared entirely. Either way, you’ll have a greater sense of choice and freedom in making your purchasing decision.

Mindfulness Has 24/7 Potential

So many people have told me over the years that when life gets hard, sitting and meditating and being mindful is even harder. Yet it is precisely during times of stress, discomfort, disappointment and confusion that mindfulness can help us the most. Having worked with a few thousand people at this point, I have come to see patterns in the way people avoid practice. When I ask people why they couldn’t meditate, they say things like, “Oh, I wasn’t relaxed enough to meditate,” or, “I wasn’t feeling happy,” or, “I was too overwhelmed.” These statements all reveal a misconception about mindfulness: that we’re supposed to do it only under conducive conditions, when we feel like it.

But the point of mindfulness is not to feel good, or to relax, or to feel calm. It is to meet our lives exactly as they are in any moment. Let’s face it: life is messy. It doesn’t operate according to our plans and good intentions. Things happen. We experience pain, both physical and mental, as well as uncertainty, ambiguity, fear, loss, praise and blame. Many of the moments of our lives are not “conducive” to peace and relaxation. Yet the invitation of mindfulness is to find our way into any situation with greater presence, focus, kindness and wisdom. In order to do this we have to practice. We have to practice every day, even if for only ten minutes. If you are in a state of despair, sit with it for 10 minutes and see what happens. Even if you spend the entire 10 minutes rocking and moaning and seething, your relationship to your despair will begin to change if you sit with it enough.

Once some years ago I rented a cabin in the Santa Cruz Mountains for a solo retreat. My plan was to spend three days in silent meditation and then return to my life in San Francisco. I arrived at the cabin in the early afternoon, unpacked my things, set up my meditation space, made a cup of tea, and then, around 4 o’clock, sat on my bench for my first session of practice. Within a few minutes I began to feel a deep sadness somewhere beneath my ribs. Soon, tears began trickling down my cheeks. When my body started to shake with sobs, I knew that this was no ordinary sadness. I fell off my bench, sobbing uncontrollably, completely crushed and shattered. As the intense wave passed, I steadied myself and sat upright on my bench again. I continued to weep, and then another violent wave shook me and I fell off my bench again, on the floor, shattered anew. When that wave passed, I sat up again, re-established my posture, and continued my practice. It went on for an hour like this. I found that as each wave of grief subsided, I could re-establish my posture and the holding of the experience in my awareness. At the end of the hour, I got up from my bench, dried my cheeks, and assessed things. I felt good, cleaned out, whole, at peace. In that moment I knew that my retreat was over.

I spent the night in the cabin, and in the morning packed my things and returned 2 days early. My sobbing session on the bench wasn’t pretty, it certainly didn’t look like meditation – but my willingness to meet the messiness inside my own heart is what allowed me to come to a deeper clarity and understanding. Mindfulness, like life itself, takes many forms.

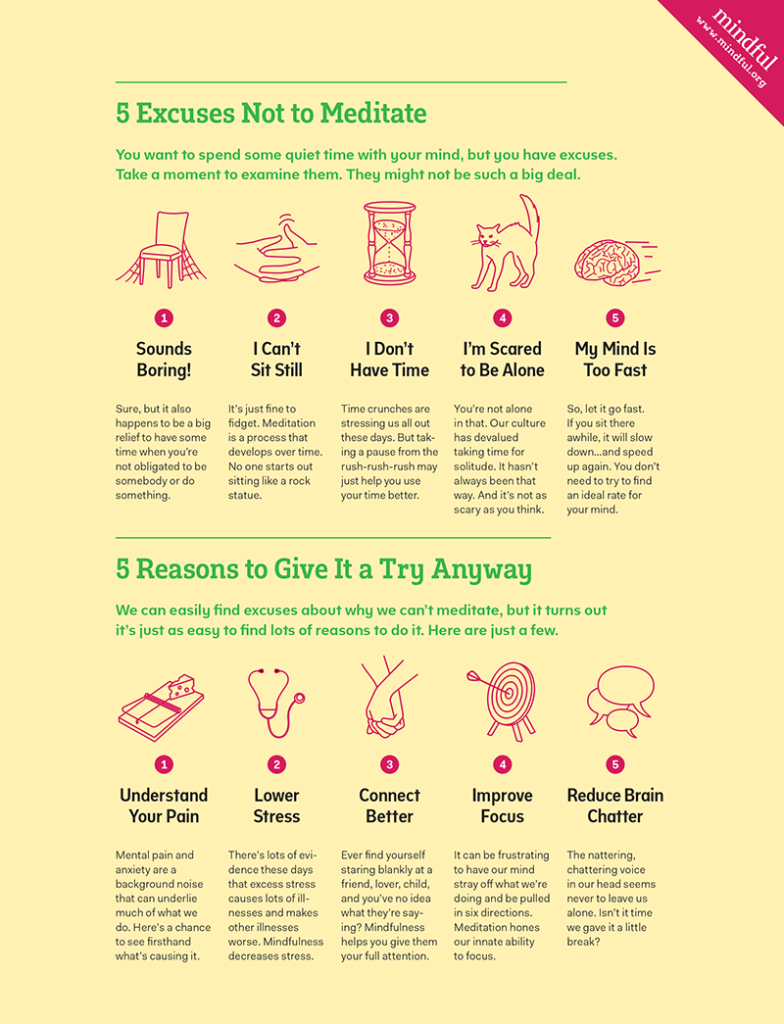

5 Excuses Not to Meditate – & 5 Reasons to Do It Anyway

A nice infographic from the folks at Mindful magazine.

Mindfulness May Decrease Racial Bias

A new study out of Central Michigan University suggests that mindfulness training can decrease bias based on race and age. Mindfulness is a skill that anyone can learn, including police officers, and it may prove to be an important component in the future of diversity training.

A story on the study can be found here. http://www.yesmagazine.org/peace-justice/study-shows-mindful-meditation-helps-reduce-racial-bias-20150806

In Relationship to Suffering

Mindfulness has been associated with so many positive things – greater focus, clarity, joy, compassion, emotional balance, resilience, general well-being, and decreased stress, to name just a few – that it’s easy to ignore one of its primary purposes. Mindfulness is essentially a practice of moving towards suffering, of coming into relationship with the challenges, traumas, anxieties and stresses, both large and small, of our lives. Because suffering is an unavoidable fact for every human being, the way we relate to it is critically important.

The moment we sit down to meditate, we force ourselves to be aware of the thoughts, stories, and emotional patterns that drive us most of the time. Many of these patterns are habitual, unconscious, obsessive, and negative. Yet they set the tone for how we respond to events. When we sit down to meditate, we also become aware of the places in the body that are tight, registering tension, or wounded. Because we are so driven by our to-do lists, our non-stop busyness makes it easy to avoid our difficulties, and to avoid our bodies and the stress signals they give us. But that avoidance conditions us to think that our difficulties are mistakes – rather than something we can be in relationship to.

Mindfulness teaches us that rather than avoiding suffering, we need to move toward it, with openness, courage, and curiosity. We become intimate with our suffering not to fix it or change it but to know it fully, to see how it effects our life. When we hang out with our fears, wounds and anxieties without needing to fix them, we bring their energy into consciousness in a way that brings us healing. We clearly see the effect that our habitual thoughts and emotional patterns have on us. We see the suffering that our minds continually create, and we see the tension and stress in our bodies as a form of that suffering. When we see these patterns over and over again through daily meditation, over weeks, months, and years, our perspective changes. Rather then believing our stories, we see that they are just mental events that don’t have to control us.

As a result of this regular intimacy with our pain, we become more whole as a result, and more free. And we start to think and act in ways that reflect that wholeness. You may not learn this in the next magazine article on mindfulness you read – but it takes courage to be mindful. Because facing our suffering is quite challenging, and also quite necessary for a fully lived life.

Not Retreating from Life

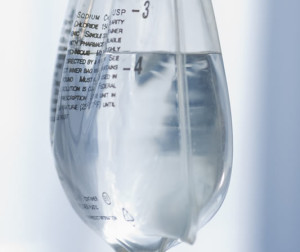

I recently returned from a 9-day intensive meditation retreat focused on the practices of concentration and mindfulness. The first four days of the retreat presented me with the usual struggle – re-learning how to slow down, quitting caffeine, abandoning cell phones, blogs and the internet, and mostly, just watching the habit patterns of my mind replay themselves ad nauseum. By day five I was really settling in nicely, my mind was calmer, clearer, and more focused, and I was able to steady my attention on the breath – and even more interestingly to me – the stillness of knowing the breath. I was really beginning to hit my stride and was looking forward to deepening my concentration in the following final days of the retreat. But on Sunday night, instead of listening to that night’s talk on practice with my fellow practitioners, I found myself in the emergency room of the nearest hospital with an IV drip of saline in my arm.

I recently returned from a 9-day intensive meditation retreat focused on the practices of concentration and mindfulness. The first four days of the retreat presented me with the usual struggle – re-learning how to slow down, quitting caffeine, abandoning cell phones, blogs and the internet, and mostly, just watching the habit patterns of my mind replay themselves ad nauseum. By day five I was really settling in nicely, my mind was calmer, clearer, and more focused, and I was able to steady my attention on the breath – and even more interestingly to me – the stillness of knowing the breath. I was really beginning to hit my stride and was looking forward to deepening my concentration in the following final days of the retreat. But on Sunday night, instead of listening to that night’s talk on practice with my fellow practitioners, I found myself in the emergency room of the nearest hospital with an IV drip of saline in my arm.

I would later find out that I had heat exhaustion. That Sunday the temperature had reached 105. The day before when it was 95 I noticed that my steps were a little unsteady, and that I was slightly light-headed. I did not understand what these symptoms might mean. I felt great otherwise and thought I was drinking plenty of water. (Later I learned that I was drinking far too little water, and even if you do walking meditation in the shade, the intensity of that heat leeches the water and electrolytes right out of you.) So that Sunday night, my body began speaking to me more loudly, and I finally had no choice but to heed its message. A kindly person from the retreat center drove me to the hospital and waited with me as I lay on a gurney in the emergency room and they triaged me, monitored my vital signs, and did blood tests. I lay there for more than two hours before anyone told me what was wrong with me. I had no choice but to allow the experience to be just as it was; no point to resist what was happening. My body was the boss, and so my mind, pliable and at ease because of five days of concentration, relaxed and let things unfold. So I lay there the whole time watching the rising and falling of my chest. On the other side of the curtain on my left a man was in the process of passing away. I witnessed the doctor explain the nature of a “devastating injury” to the man’s family. Down the hall to my right, another man may have been dying as well (we never found out for sure) and doing it very loudly, with lots of screaming and pain. The screaming went on for about a half hour. And then there was a chilling silence. In the meantime emergency room nurses, doctors and technicians rushed back and forth, doing the best they could. As I lay there I understood then that I was in the midst of life. Or, as they say in Zen, in the midst of the great matter of birth and death. The gurney was now my practice cushion.

When I learned that I had heat exhaustion, was stable, and could go, I rose from the gurney as if a stranger in a strange land, filled with gratitude and sadness. Later, back on retreat, I reminded myself that you never get the retreat experience you want – maybe not even the one you need. When you go on retreat, birth and death do not stop happening, they just change their form. If anything, being on retreat is really just a way of experiencing life more directly, with more intensity. Retreat is just one form that life takes – but wherever you are, life doesn’t stop being life. It never does.

Great is the matter of birth and death,

All is impermanent, quickly passing.

Awake! Awake!

Don’t waste this life.

The Meditating Brain

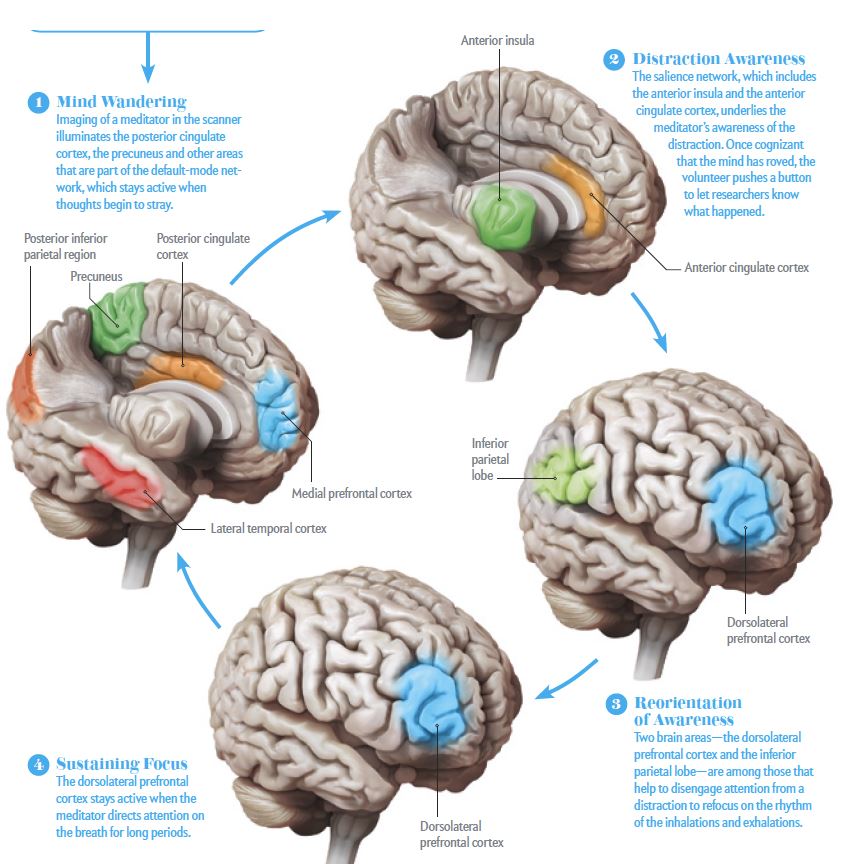

This is a great graphic from an article in Scientific American showing the different regions of the brain that light up during the different phases of the meditative process. From focused attention, to mind wandering, to awareness of wandering and redirecting of attention.

Work Life Balance is an Activity, Not an Event

Seeking Perfection in the Midst of Change

“Work Life Balance” is a popular theme in today’s always on and information-loaded workplaces. We are told that work and personal life are two powerful forces that we should strive to bring into balance with each other. As if work life balance were an external goal that can be realized if only we balance the scales properly. But life is always changing. Our jobs change, our colleagues change, the economy changes, industrial conditions change, our bodies change, our minds change, our families and friends change, the world changes….Is there anything in life that doesn’t change? And because conditions are always in flux, we will always need to make changes to our own personal scales of work life balance.

An Inner Equilibrium

Instead of thinking of work life balance as an external state to achieve, it may be more useful to think of it as an inner equilibrium that we can cultivate every moment we are alive. Like a tightrope walker who is constantly making micro-adjustments to keep from falling, work life balance becomes an ordinary activity that we can do all the time to make sure that we are living our lives sustainably.

To Understand What is Needed

An example of work life balance may be something as simple as remembering to notice your breath during a meeting, or turning off notifications on your smartphone when you get home from work, or driving to work without the radio on to build greater focus while you commute, or consciously choosing to say no to that event invite that is just one too many, or remembering to call old friends you’ve been wanting to catch up with, or deciding to put your work down and go for a walk. Above all, work life balance is about being sensitive enough in each moment to understand what is truly needed.

How Mindfulness is Short Changed in Popular Culture

The glib and tongue and cheek video from the BBC below is a good example of how mindfulness is being covered in the media. A lot of what is seen in this video is actually informative, but something is missing in its discussion of mindfulness which is also missing in other popular depictions of the practice. The typical way of presenting mindfulness is that it’s all about living in the now. As one of the subjects of the video says, a breath doesn’t take place in the past and it doesn’t take place in the future. A breath can only take place now. So mindfulness is about being aware in the present moment. But mindfulness is about more than awareness and the present moment. The sociologist in the video who criticizes mindfulness as a form of escapism likely doesn’t have a mindfulness practice himself; but he’s pointing to a flaw in how mindfulness is presented.

If mindfulness is just about being in the now, after all, how does that possibly help us deal with the practical challenges of living? Good question. The truth is that mindfulness has always been about two things: awareness and clear comprehension. Clear comprehension is a critical element in being mindful: it is our capacity to discern what is true in our direct experience, especially as it relates to suffering and freedom from suffering. When we are aware of our breath, we are not just aware of a featureless present moment, void of content; we are also aware of the patterns of our minds that cause us stress, panic, and pain. And because of this discerning aspect of mindfulness, the choices we make start changing in response to what we are learning about what causes suffering in our lives. Those new choices then start to change our lives in very practical ways. We see through old, unhealthy patterns and disidentify from them, thus giving ourselves freedom to choose a different course. Far from passive escapism, mindfulness is about choosing the appropriate response.

Like Clouds Passing

The human mind is beautiful, but also dangerous. Our thoughts and emotions can be powerful drivers of our behavior. Since many of our mind-states are negative, our actions are often at the mercy of our thoughts. Gloomy and pessimistic thinking, long established from habit, creates rigid and stereotyped narratives psychologists have labeled cognitive distortions. You probably know some of these stories from your own experience. They often begin with, “I’ll never be good at this because,” or “I’ll never be loved because,” or “My pain will always be like this because,” etc. These stories become so familiar to us that they define who we think we are or can become. And the actions we take in the world reflect the limitations of this thinking.

The human mind is beautiful, but also dangerous. Our thoughts and emotions can be powerful drivers of our behavior. Since many of our mind-states are negative, our actions are often at the mercy of our thoughts. Gloomy and pessimistic thinking, long established from habit, creates rigid and stereotyped narratives psychologists have labeled cognitive distortions. You probably know some of these stories from your own experience. They often begin with, “I’ll never be good at this because,” or “I’ll never be loved because,” or “My pain will always be like this because,” etc. These stories become so familiar to us that they define who we think we are or can become. And the actions we take in the world reflect the limitations of this thinking.

But negative thinking itself isn’t the problem; it’s how we relate to our thinking that’s important.

One of the most powerful things about mindfulness practice is that it gives us the space to observe and witness the activity of our minds directly. With mindful awareness we see that thoughts come and go constantly, they can’t be held onto or controlled. We see that thoughts are not solid or fixed, that they are not our destiny, that they aren’t facts that force us to act, but are rather like clouds passing through the sky of awareness. With this perspective, which is cultivated through regular mindfulness practice, thoughts are seen to be ephemeral events in consciousness. When we see the impermanent nature of our thoughts, we begin to dis-identify with them. With this increased awareness, we have a choice about how we relate to our minds. And since thoughts and emotions drive much of our behavior, when we make the mindful choice to focus on thoughts that serve us instead of hurt us, our actions in the world will more likely be of benefit to ourselves and others.

Mindfulness and the Art of Giving Space

Talk: San Francisco Insight Meditation Community, May 24, 2015